Guest Post: Gregory Duhl on Introducing AI Tools in the First-Year Contracts Course

All In on AI: Reimagining How We Teach Contracts

[Note: This post summarizes a longer article available on SSRN. For the research in support of this approach and the pedagogical framework for the class, see the complete article.]

For over the past year now, I have observed the tension among my colleagues between advocating for students to use generative artificial intelligence to enhance learning and banning or monitoring AI use to prevent cheating. After twenty-four years of teaching, and with AI transforming legal education and the legal profession, I felt as if I was doing my students a disservice by continuing to deliver my courses following traditional methods without accounting for the drastic changes in legal practice.

This feeling made adding a single AI exercise to my first-year Contracts course feel both superficial and inadequate. At the same time, prohibiting AI use outright was equally unrealistic. Many transactional lawyers already rely on tools that automatically generate, benchmark, and revise contract language. The practice landscape has shifted, even if doctrinal pedagogy has not. In addition, the research suggests that students, particularly neurodiverse students, students with disabilities, and non-traditional students, benefit from the personalized learning and academic support that AI offers.

So instead of retrofitting AI onto a traditional Contracts course, I rebuilt the course from the ground up. The goal was to refocus learning by moving students away from the rote tasks AI can now perform and toward the higher-order judgment, nuance, and error-spotting that define what human lawyers must still do. I also wanted to transform my role from that of a teacher to that of a facilitator or architect of student learning.

The resulting design centers on a straightforward premise: Contracts students must learn how to supervise, critique, and outperform AI because, in actual practice, that is already part of the job.

Why Redesign Contracts at All?

AI can already perform many of the lower-level tasks we traditionally ask 1Ls to do in Contracts: articulate basic rules, answer straightforward questions, generate the first drafts of written analysis or contracts. But AI struggles with what makes contract law challenging: precise rule application, doctrinal nuance, judgment, error-spotting, and strategy. Far from eliminating the need for the course, this reality pushes these higher-order skills to the foreground.

If AI can generate a reasonable answer to a bar-style Contracts essay (which we know it can), then a pedagogically responsible Contracts course must explicitly teach students how to supervise that output. This requires moving beyond “AI or no AI” debates into a structured approach where students interact with AI, critique AI, and outperform AI. This is the driving principle for every assignment in my redesigned course.

A Course Built on Continuous AI-Supported Practice and Human Judgment

First, let me clarify the nature of the course: while it integrates AI exercises throughout, it also includes low-stakes, formative quizzes across the semester that test doctrinal understanding and application and give students practice for the final examination. A final examination, which, along with the quizzes, count for 40 percent of the students’ course grade, is a closed-book, multiple-choice exam (with past Multistate Bar Exam questions) that replicates the format and time and technology constraints of the bar examination. This ensures that students develop the independent analytical skills required for bar passage while also learning to supervise AI effectively in practice contexts. The AI-embedded assignments count for the other 60 percent of the students’ course grade.

I am specifically highlighting the assignments that embed AI in this post. The redesigned course uses six scaffolded categories of exercises, each building on the last. All share three characteristics:

- Students must use AI but cannot rely on it.

- Assessment measures the value the student adds over the AI.

- Human judgment, including doctrinal specificity, analytical precision, and structural logic, is always the core competency tested.

Below is an overview of the major components and why they matter.

1. Prompt Engineering and Supervisory Skills (Week 1)

Students begin with a short, pass-fail assignment designed to teach the foundational skill for all subsequent work: controlling, correcting, and refining AI output. Using a simple biography, students must rewrite content in different specified tones by constructing a multi-part prompt (the “Setup Block”). The lesson focuses on supervisory control: understanding that without precision in prompts, AI generates unfocused, error-prone work. This early exercise sets the expectation that students are responsible for what the AI produces, just as lawyers are responsible for what appears in their filings even if AI generates a draft.

2. Socratic Dialogue Bots to Scale Doctrinal Reasoning (Six Times During Semester)

Traditional Socratic pedagogy offers real-time reasoning practice to only a handful of students. AI enables scaling. Six times during the semester, students engage in a 10–15-minute Socratic dialogue with a custom-trained bot that draws from assigned readings.

Students must upload the full transcript. I read these transcripts to identify patterns in student misunderstandings and intervene in subsequent classes.

The benefit for Contracts is substantial:

- every student must articulate rules and apply them;

- every student receives immediate challenge and feedback;

- no student can “hide in the back row.”

These dialogues function as private written exchanges on cases and doctrine, and they consistently can reveal analytical gaps that in a traditional class might only emerge on midterms or finals.

3. Bot Building as Mastery Assessment (Week 3)

Students then reverse roles: they must teach doctrine to a machine.

The assignment: build a simple teaching bot able to instruct another student on the doctrine of consideration and its exceptions. To do this well, students must:

- structure doctrine hierarchically,

- articulate rules precisely,

- anticipate user questions, and

- catch their own doctrinal gaps.

Research on the “protégé effect” confirms that preparing to teach produces deeper learning than passive study. That principle maps cleanly onto Contracts, where precisely articulating rules and its exceptions (consideration, promissory estoppel, preexisting duty rule, etc.) is essential.

4. AI-Assisted Bar Essay Writing (Week 5)

This assignment directly responds to concerns that AI will prevent students from learning how to analyze. It occurs in three phases:

Phase 1: AI Draft

Students design a sophisticated prompt and instruct AI to produce an IRAC essay based on a past California Bar Examination Contracts exam question (the “Fence” fact pattern).

Phase 2: Human Revision

Students must revise the draft using Track Changes, fixing

- imprecise rules,

- missing issues,

- conclusory applications,

- misinterpretations of facts.

Phase 3: Human-Only Timed Essay

Students then write a closed-book, 60-minute essay with no AI assistance. Assessment focuses on phases 2 and 3, not the AI output.

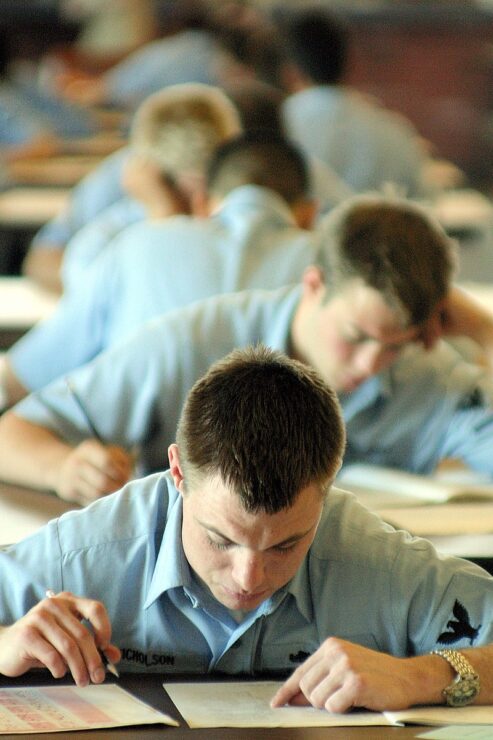

030316-N-3228G-002.PEARL HARBOR, Hawaii – (March 16, 2003).Nearly 250 E-5 candidates mark their answer sheets while taking the March 2003 advancement examination at Club Pearl Complex. A total of 701 candidates took the test island-wide in Navy Region Hawaii and included shore commands and temporarily assigned Sailors from deployed Pearl Harbor ships and submarines..U. S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 1st Class (AW) William R. Goodwin..

This is a human-in-the-loop model; that is, a structure in which AI handles routine or mechanical drafting tasks while the human (student) remains in the loop and supervises, verifies, and ultimately exercises the judgment that the tool cannot replicate.

5. Judicial Opinion Assignment: Verification and Hallucination Detection (Week 7)

One of AI’s most significant risks for lawyers is its tendency to hallucinate authority. The judicial opinion assignment forces students to confront that risk head-on. Students receive:

- the complaint, answer, and contract in Hutter & Associates Inc. v. Hyde Brewing Co., a case turning on whether a construction agreement is a contract or an agreement to agree.

- a video of the oral argument in the case before Judge Robert McBurney, a Fulton County, Georgia, Superior Court judge.

- An assigned jurisdiction whose contract-formation law they must research.

Using Lexis+AI, Westlaw AI, or Bloomberg Law, students must draft a judicial opinion on cross-motions for summary judgment. The value for Contracts is obvious: Formation disputes turn on doctrinal nuance, fact specificity, and the interplay of objective manifestations of assent; areas where AI often oversimplifies or misapplies rules. This assignment teaches students to treat AI research as a starting point, never an authoritative source.

To receive any credit, the final draft cannot include a single hallucinated citation. Students must also submit a Prompt Management Tree documenting how they iterated prompts to correct inaccuracies.

6. Spellbook Contract Drafting and Negotiation Series (Weeks 8–14)

AI contract drafting tools like Spellbook are increasingly common in practice. The second half of the semester trains students on how to use them responsibly and critically. Here’s the four-part progression:

A. Benchmarking Exercise (Week 8)

Students use Spellbook to evaluate a provided Non-Disclosure Agreement against market terms. They must decide which suggested changes matter and why; it’s an issue-spotting exercise focused on contractual risk.

B. AI-Assisted Negotiation (Week 10)

Students represent Lumon Inc. in negotiating a Master Services Agreement. Spellbook’s “Negotiate” and “Ask” functions surface risk, suggest alternative terms, and highlight deviations. Students must decide which suggestions to accept, reject, or modify.

C. AI-Assisted Drafting of Complex Employment Agreement (Week 12)

AI produces an initial draft, but students must revise it extensively in Track Changes. The goal is for students to understand that while AI can draft language, it cannot supervise itself, handle nuance, or align contract terms with client priorities.

D. Capstone: Landlord–Tenant Negotiation and Agreement (Week 14)

In pairs, students negotiate a resolution to a simulated commercial lease dispute and produce a final agreement using AI as a tool, not a drafter of last resort.

Across these Spellbook assignments, students learn core transactional skills: managing risks, drafting clear language, identifying client priorities, and judgment. But throughout the entire semester, students are using AI to enhance skills emphasized in a traditional first-year Contracts course: reading and analyzing cases, applying the law to hypothetical facts, mastering doctrine.

Does This Course Redesign Take it Too Far?

Most colleagues who hear about this redesign begin with skepticism. That skepticism is healthy. It mirrors the concerns I address more fully in the article:

- Will students still learn foundational analytical skills?

- Will they pass the bar?

- Will they become over-reliant on AI?

- Is this scalable beyond Contracts?

The short answer is that every assignment requires more student reasoning than the previous, traditional version of the assignment. AI handles what lawyers increasingly delegate to junior associates (and increasingly sophisticated AI tools); students handle what distinguishes human lawyers: judgment, including argument development, factual nuance, precision, risk management, and strategy.

Because participation is uneven in a traditional course, students who need the most analytical practice often receive the least of it. An AI-integrated course forces students to analyze dozens of hypos and answer dozens of questions with immediate feedback and structured supervision.

Scalability and Grading

The enrollment for the course is currently 60 students. Colleagues often ask whether this design is manageable at scale. The answer is yes, but it requires rethinking how instructor time is allocated:

First, the course design work happens up front. Once assignments, bots, and rubrics are built, they require minimal adjustment semester to semester. The shift away from extensive lecturing, questioning, and class discussion and toward facilitation frees up time during the semester itself.

Second, strategic use of rubrics makes grading efficient. Rather than line-editing or giving detailed comments on submissions, I will use rubrics organized around broad categories (issue identification, rule precision, application quality, conclusions). AI-supported assignments lend themselves particularly well to this approach because the core question is always: What value did the student add over what the AI produced?

Third, the goal is not to provide individualized feedback on every assignment to every student. The goal is to intervene with the students who are struggling most. The Socratic dialogue transcripts, formative quizzes, and early assignments surface these students quickly, allowing targeted support where it matters most.

Whether this redesign works and actually improves doctrinal retention and analysis is an empirical question. I am conducting a pilot study in Spring 2026 to measure outcomes systematically.

Final Considerations

AI is not going away. Contracts pedagogy can either ignore it, prohibit it, or embrace it. This course adopts the last approach: integrating AI in ways that strengthen the teaching of contract doctrine, analytical skills, and transactional competence.

If AI is now a routine part of contract drafting, review, and negotiation, then a Contracts course must explicitly teach students how to use it, question it, correct it, and—most importantly—outperform it.

The article provides the research to support this approach and my personal journey in designing the course. I welcome conversation, adaptations, and critiques from colleagues who wish to experiment with similar models or who want to run as far away from this model as possible.