Connecticut Court Finds no Implied Contract for Whey

If this weren’t so long, it would make a great teaching case on requirement contracts, the Statute of Frauds, and course of dealing.

Ultimate Nutrition, Inc. (Ultimate) claims to have bought over $30 million in whey products from Leprino Food Company (Leprino) over a 25-year period for its nutritional supplements. Ultimate made its purchases quarterly and then supplemented those quarterly orders with spot sales. The parties would estimate quarterly needs in advance. Ultimate would then notify Leprino of its precise needs about one month before quarterly deliveries were due, the parties would agree to a price, and Ultimate would pay for the prior to shipment of pickup. When Leprimo made spot sales, the delivery date was close to the date of the purchase order. Leprino was not Ultimate’s only supplier of whey products

Ultimate would sometimes ask Leprino to delay its deliveries. This practice was known as a rollover. Rollovers did not affect purchase prices, and Ultimate still paid the original agreed-upon price prior to delivery. Although Leprino disfavored rollovers, they became common with Ultimate. There were no rollovers in 2018, 2019, or 2020, but the parties began to have disputes over Ultimate’s requested rollovers in 2021. This was during a period when whey prices increased by 150 percent. Ultimate wanted to roll over orders from the first quarter of 2021 into the third. It then wanted to roll over some of its second quarter orders as well. Towards the end of the third quarter, Leprino refused to enter into negotiations over fourth quarter deliveries until Ultimate committed to accepting delivery of its third quarter orders. Receiving no commitment, Leprino cancelled existing orders and terminated its relationship with Ultimate.

The case arrived in the U.S. District Court for Connecticut on diversity grounds. Ultimate alleged a breach of an implied long-term contract as well a breach of contract on purchase orders for quarters 1 and 3 of 2021. The complaint also alleged breaches of the duty of good faith and fair dealing, plus statutory violations.

In Ultimate Nutrition, Inc. v. Leprino Food Company, the District Court granted Leprino’s motion for summary judgment on all claims and entered judgment for Leprino. Because the complaint relates to contracts for the sale of goods, Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) applies. Because the contracts and the alleged implied contract were for goods valued in excess of $500, the Statute of Frauds applied.

The claim for breach of an implied-in-fact contract alleged the existence of a supply contract between parties established through course of dealing. Leprino allegedly breached by terminating that implied agreement without sufficient notice as required under UCC § 2-309(3). The Court rejected the idea of an implied supply contract for two reasons, both of which it relates to the Statute of Frauds. The easy case for Leprino is that Ultimate alleges a contract for goods for $500 or more, and the contract is not evidenced by a writing. Interestingly, the Court also finds that the Statute of Frauds is violated because the parties’ alleged implied agreement states no quantity term and is not a requirements or output contract. That makes perfect sense, although I think the question of whether this is a requirements contract is closer than the Court allows, but I don’t see what that’s got to do with the Statute of Frauds. A contract without a quantity term cannot be enforced, whether or not the Statute of Frauds is implicated. I suppose the point is that the written agreements are incomplete in that they don’t state a quantity term.

Ultimate argues that the Court should recognize the common-law exception to the Statute of Frauds for part performance. The Court rejects the argument, finding that the UCC has its own part-performance exception to the Statute of Frauds that applies only with respect to goods for which payment has been made and accepted or which have been received and accepted. Nor is the Court willing to treat the alleged implied contract as “indivisible.”

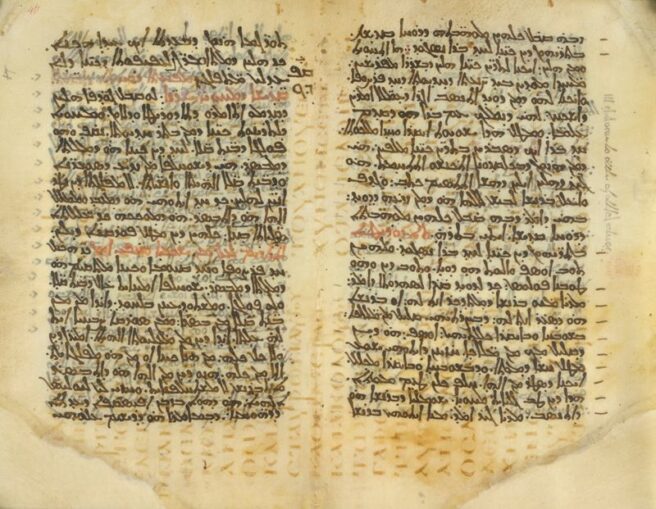

I am ambivalent about the argument that the UCC’s part-performance exception supersedes the common law version of that exception. I tell my student that the UCC is like a palimpsest (below), a text written over another text but through which the original text is still visible. The common law thus fills in gaps where the UCC is silent. Absent some reason to think that the UCC meant to displace the common law, the common law still applies. So, for example, the UCC’s rule for firm offers creates a new way to make an offer irrevocable, but it does not displace the common law option, which enables the offeree to make the offer irrevocable by giving consideration in exchange for the offeror’s promise to hold the offer open.

The text of the UCC does not, to me at least, evidence an intention on the part of the UCC’s drafters to replace the common law part-performance exception to the Statute of Frauds with a narrower exception. There are in fact two narrow exceptions, as the exception for specially manufactured goods is also a part-performance exception. Because I hate the Statute of Frauds and love the UCC, I am inclined to believe that the UCC’s drafters wanted to narrow the Statute of Frauds as much as possible. They did so by creating four new exceptions to the Statute of Frauds. Why would they, in so doing, want to eliminate existing exceptions? If any readers familiar with the legislative history of the UCC have contrary views, I’d love to hear them. We no longer have comments, but e-mail works fine.

It is of no matter in this case. There could be no “part-performance” of an implied contract that lacked a quantity term. Rather, the parties had only quarterly contracts, which built on a long-term relationship that was never a long-term contract for reasons that have nothing to do with the otiose Statute of Frauds.

The Court does a fine job with the claims for breach of the parties’ short-term contracts. Ultimate argued that, although the parties’ agreements referenced specific quarterly delivery dates, the express terms had to be supplemented with evidence of the parties course of dealing, in which Leprino allowed for dozens of rollovers. The Court appropriately denied Leprino’s motion to dismiss so that it could consider course-of dealing-evidence. However, now having considered that evidence, the Court found that Leprino had discretion to allow rollovers or refuse them. No reasonable jury could conclude that Ultimate was contractually entitled to rollovers. Ultimate’s usage of trade evidence was similarly unavailing.

Having so concluded, the Court spends relatively little space on the good faith and fair dealing and statutory claims. Those claims arise based on the same factual allegations, and they too cannot survive the motion for summary judgment.